The EBSNS marks the passing on Friday, 12 April, of Robert MacNeil (1931-2024). He had a long and storied career as a journalist and a writer of a wide-range of books. He is most well-know for his time on PBS as part of the MacNeil-Leher Report. I met Mr. MacNeil in the mid-2000s, in Port Medway at a literary event and learned he was a huge fan of Elizabeth Bishop. He learned about the EBSNS and the EB House and through his efforts, he secured a significant grant from an American media organization for the EBSNS, which used it to construct the historical pergola that still exists in Great Village, and to publish the walking tour booklet that has been distributed far and wide. I met him again in the 2010s, around the time of the EB Centenary celebrations in Great Village, as was able to give him a tour of the EB House. The EBSNS owes Robert MacNeil a debt of gratitude for his generous support of the society's work.

Sunday, April 14, 2024

Sunday, March 3, 2024

“My Permanent Home Some Day”: Elizabeth Bishop in Key West by Brian Bartlett

The kind of travel called literary pilgrimage has been around for a long time. We perform it to honour beloved writers, get closer to their experienced worlds, or sharpen our feelings for specifics of particular poems or novels. Many have travelled from afar and watched plays in the Globe Theatre, stood (or knelt) by Baudelaire’s grave in the Montparnasse Cemetery, or toured Katherine Mansfield’s childhood house in New Zealand. To cite personal examples, I’ve visited Willa Cather’s house in Red Cloud, Nebraska, Jack London’s forest retreat north of San Francisco, Hawthorne’s seven-gabled house in Salem, Marianne Moore’s address in New York, Wordsworth’s Dove Cottage, the homes of Keats and Dickens in London, John Muir’s origins in Scotland, multiple statues of Dante in Italy, and Pessoa’s house and favourite bar in Lisbon. Some day I’d like to breathe the air of the one house Emily Dickinson knew intimately, and follow routes Basho and Issa took through Japan.

It would be easy to mock literary pilgrimages, and to consider

them superficial, tempting travellers into boastfulness of the I-was-there-where-they-walked sort, with

no bearing on the real substance of reading and re-reading. Yet I’ve found that

spending even an hour in the wind and dampness on the Haworth moors impressionistically

enhanced my next reading of Wuthering

Heights; and having a meal in Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, Johnson’s favourite

pub—despite many changes since the eighteenth century—helped evoke the

atmospheres of his many lively conservations there, including ones put on paper

by Boswell. Still, because I’ve often felt an inward need to defend

writer-based tourism, it seems clear that I also wonder if it’s self-indulgent

and sentimental. Lived experience, however, and a desire not to belittle the

pleasures of other travellers, help me take a more tolerant view.

*

When Elizabeth Bishop first visited Key West in December

1936 shortly before her twenty-sixth birthday, she and Louise Crane made the

trip by charter boat. Bridges and motorways didn’t connect all the hundred-mile

length of the Florida keys curving south-westward into the Gulf of Mexico. A

year earlier the Flagler Railroad’s bridge had begun providing chances to reach

the final, most southern of the keys by train, but late in 1935 a severe hurricane

walloped Key West and dismantled the bridge. When I travelled to Key West for

the first time in early 2024, at the age of seventy, it was along a highway

overseen by seabirds such as Magnificent Frigatebirds silhouetted high in the sky

and—closer to the cars, trailers and RVs—Brown Pelicans (“whose delight it is

to clown,” Bishop wrote in her poem “Florida”). If she’d lived long enough to

see Key West in the twenty-first century, Bishop would’ve recognized many of

the area’s creatures, architectural beauties and prismatic water-and-light

colours, yet the city’s growth might’ve estranged her. In an interview she recalled

of the Key West she first observed: “The town was absolutely broke then.

Everybody lived on W.P.A.” The

inexpensiveness of living there was part of is appeal; her first rent room cost

only $4.00 a week. Now Key West is so expensive that my wife, a friend of ours and

I stayed for two nights a few islands away on Sugarloaf Key, and drove a half

hour to the much more famous key during the day.

(BROWN PELICAN)

Bishop lived in Key West much of the time between 1938 and 1949—before, during and after World War II, and especially in winter. Those years helped develop her fondness for tropical climates and locations away from unrestful cultural mainstreams; Thomas Travisano has suggested a link between Bishop’s cherished, much smaller childhood community in Nova Scotia and the Florida city, “a warmer and more bohemian Great Village.” Attracted to maps and considerations of longitudes and latitudes (see her early poem “The Map” and the introductory quotation beginning Geography III), Bishop might’ve found it apt to choose the extreme southern tip of the continental United States as a place for exploration, relaxation, friendship and writing. She also valued southern Florida for the abundant opportunities to fish and swim, and for the relief she felt from her chronic asthma—but also for its death-haunted, unfamiliar phenomena, such as dozens of vultures circling “like stirred-up flakes of sediment / sinking through water” and dead mangrove roots that “strew white swamps with skeletons” (images from “Florida”). Though Bishop was far from the most gregarious of people, Key West also served as a writer-friendly place to her, since Hemingway and John Dos Passos were well-known residents, and in the winter of 1935 both Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens had begun spending winters there. Stevens had written one of his greatest poems, “The Idea of Order at Key West,” in the same year Bishop first set foot on the key.

Over seventy years after Bishop’s Key West era ended, I spent a mid-January afternoon tracking down the locations of her residences there, with the brochure Key West Homes of Elizabeth Bishop (text by Kay Bierwiler) in hand. The addresses were within walking distance of each other in that comfortably walkable city. The first stop on the route was 529 Whitehead Street, where Bishop roomed during her first Key West winter, in early 1938. I couldn’t tell whether the building where she roomed had been torn down and replaced, or radically renovated. The address now is for IVs [I.V.s] in the Keys: Essential Hydration Therapy (which specializes in intravenous treatments injecting liquids containing minerals, nutrients and antioxidants). Across the street from Bishop’s room was a courthouse and a jail. Her first Key West residence and its surroundings fuelled her writing: “I am doing absolutely nothing but work,” she wrote to Marianne Moore, “scarcely even read.” She wrote her first Key West poem, “Late Air” (“the radio-singers / distribute all their love songs / over the dew-wet lawns”) and encountered her second landlady’s memorable bossy servant, Cootchie (inspiration for a 1941 Bishop poem named after her; Key West initiated Bishop’s interactions with racially mixed communities). A block away stands the Green Parrot Bar, inviting with its colourful exterior paintings of its namesake. With origins as far back as 1890, the bar began as a grocery store and continued so until nearly mid-century; Bishop must’ve shopped at it for local food such as grapefruit, lemons and oranges.

With my two travelling companions that morning I’d already spent an hour a few blocks away on Whitehead St., at 907, the most famous address in Key West. Its basic structure built in 1851, Hemingway House is an example of French Colonial Architecture. In differing accounts, I’ve read that Pauline Pfeiffer Hemingway, Ernest’s second of four wives, once a writer for Vanity Fair and Vogue, bought the house; or she persuaded her uncle to do so and give it to her and Ernest as a wedding present. Husband and wife lived together there between 1931 and 1939; by the time of their divorce in 1940, Ernest had moved to Cuba, but Pauline remained in the house for eleven more years. Bishop’s time in Key West was mostly a decade later than Hemingway’s. While 529 Whitehead was her first address in the city, 907 was one of her last residences, for the winter of 1947-48. She was friends with Pauline (“the wittiest person I’ve ever known, man or woman”), but Pauline was away during Elizabeth’s stay. The poet enjoyed many aspects of the property, including the unusually large, expensive swimming pool, which featured underwater lights (as quoted in Bierwiler’s brochure, Bishop wrote that friends in the pool “looked like luminous frogs”). Years before her brief sojourn in the Hemingway House, in another Key West house Bishop had written “The Fish,” a poem she was pleased Hemingway praised. Though Bishop and Hemingway both honoured piscine strength and struggles, her descriptions of an old fish are far more lavishly detailed than anything in adjective-avoiding Hemingway’s later novella The Old Man and the Sea, and her poem ends with an unHemingwayesque line: “and I let the fish go.”

(SLOPPY JOE’S BAR)

A now legendary Key West spot, Sloppy Joe’s Bar, opened in 1934 on the day Prohibition was repealed, then moved to its current location in 1937, less than a year before Bishop’s first Key West winter. The bar’s and Hemingway’s names are forever linked, yet young Bishop also spent evenings with friends there, chatting and drinking and dancing the rumba. We can choose to accept or question James Merrill’s report or belief that the often subdued poet would “jot a phrase or two inside the nightclub matchbook before returning to the dance floor.”

The Key West address most associated with Bishop is 624 White Street. In spring 1939 Bishop

and Crane bought the handsome nineteenth-century clapboard house there. Bishop

wrote to Moore: “…seems perfectly beautiful to me, inside and out.” Then the

house was isolated, with a yard enlivened by many kinds of trees—banana,

avocado, sour sop, lime and mango. Years later it would be recognized as one of

the three “loved houses” alluded to in Bishop’s villanelle, “One Art.” Its

initial calm helped Bishop concentrate to finish most of the manuscript of her

first collection, North & South, by

the end of 1940 (though the book didn’t appear in print until 1946). In mid-century,

Key West was a quieter location than it is today, yet even by 1941, Bishop had

grown so annoyed by nearby construction and traffic noise that she moved away

and began renting the house; five years later she sold it.

The White Street house is the one Key West Bishop location

explicitly identified as such for passers-by. A “Literary Library Register”

bronze plaque of Friends of Libraries USA spells out the historic significance

of the building, and quotes Bishop’s lines, “Should we have stayed at home, / wherever

that may be”? On a larger scale, a much

more complicated sign announces: “The non-profit Key West Seminar acquired the

property in 2019, and is now restoring the house to its historic condition,

drawing upon Bishop’s private papers and photographs.” For that reason, the

house is now closed to visitors. The sign also includes reproduced images of

the house: a photo of it from Bishop’s time, and a painting of it by local folk

artist Gregorio Valdes (1879-1939). Bishop commissioned Valdes to do the painting.

Soon after his unexpected death in the next year, she wrote an affectionate essay

about him and his art (found in both Collected

Prose and Prose.) The sign in

front of the house is misleading in one respect: it speaks of Bishop “living in

this house between 1938 and 1946,” but she lived elsewhere between 1941 and 1946.

(WHITE STREET SIGN)

After her time with Crane on White Street and months of living in New York, in spring 1941 Bishop met Marjorie Stevens, into whose apartment at 623 Margaret Street she soon moved. Bishop’s alcoholic lapses had intensified; she spoke of “New York troubles,” and wrote that she was “very glad to be back” in Key West. She and Stevens lived on Margaret Street all that summer, and for much of the next three years. Between March and September of 1942, partly due to their growing disenchantment with the mounting military presence in Key West, they travelled around Mexico. In the following summer, sounding bored and guilty over her inactivity, Bishop got a job grinding binoculars for a U.S. Navy optical shop, but eyestrain “made me sea-sick, & the acids used for cleaning started to bring back eczema,” so the job ended after five days. The Margaret Street house was very close to the city’s spacious, tree-shaded cemetery (which I walked through after finding the street). Much later Bishop wrote affectionately of the Great Village cemetery of her childhood; first, while living in Florida, she painted at least three watercolours of spots in the Key West Cemetery (reproductions of them are in the book of her art edited by William Benton, Exchanging Hats: Paintings).

As for 623 Margaret, no such address appears to exist

anymore. All I could find was a large tree against a background of exuberantly

sprawling greenery. But I paused at its former location, moved to remember that

it was where Bishop likely wrote her posthumously published, warm-hearted and

richly atmospheric love poem (likely for Marjorie), “It is marvellous to wake

up together.”

A beautiful house still stands at 630 Dey Street. Now lemon-coloured, white-posted-and-fenced and sky-blue-shuttered, this was Bishop’s home base for a short while in 1948. It belonged to her older friend the philosopher John Dewey, a man she felt such deep affection for that she compared him in letters to other loved persons in her life, grandfather Bulmer and Marianne Moore. (Earlier, in the summer of 1946 during a few weeks in Canada, Bishop had visited Dewey for a day at his summer house in Hubbards, Nova Scotia. For her poetry those weeks were crucial, providing material for two of her masterpieces, “At the Fishhouses” and “The Moose.”). I’m unsure whether it was Dewey or his physicist daughter, Jane, also a friend of Bishop’s, who invited her to stay in the Dey Street house It was under its roof that she wrote her key poem (no pun intended) “The Bight.”

Another white house still stands at 611 Frances Street; the address is by a door far back from the

sidewalk. Bishop rented an apartment there in the winter of 1948-1949 and seemed

pleased by its “screened porch up in a tree, & a view of endless waves of

tin roofs and palm trees.” One thing had come full circle: Mrs. Pindar, the

initial landlord of Bishop’s first Whitehead Street residence over a decade

earlier, also owned the Frances Street house.

(THE BIGHT)

Many roosters roam the streets of Key West. We heard that the city appears to have something of a love-hate relationship with the birds. A special bonus on my solo touring of the city with Bishop in mind was an encounter with an extraordinary rooster. Its feathers ranged from white to yellow and gold, from rust to red, from navy blue to paler blue inflected with purple. It was an entertaining fantasy to imagine Bishop encountering such a rooster in 1941 on that very street before writing “Roosters,” her biting satire of militarism and macho pride.

(ROOSTER)

In the honeymoon phase of Bishop’s attachment to Key West, she suggested in a letter that she hoped it “will be my permanent home some day.” Her search for suitable places for her writing to thrive, her restlessness and curiosity, her economic needs, health troubles and complicated relationships prevented her from ever finding a place to settle into for decades. After Key West, she spent periods of widely varied durations in New York, Maine, Rio de Janeiro, Samambaia, Ouro Preto, Seattle, San Francisco and Boston. Even spending a few hours in Key West, however, can give a heightened sense of why she might’ve dreamt of the island as a place to stay.

In the context of literary pilgrimages, I didn’t travel to southern Florida primarily to visit a poet’s houses. Above all, the journey was a chance to visit a friend, explore the Everglades and the area around Vero Beach, and see first-hand the breathtaking biodiversity of southern Florida, despite great diminishments in its natural environments over the past century. Our excitements included hours in the presence of palms and mangroves (multiple species of both), herons and egrets and ibises (multiple species), spoonbills and cranes, vultures and anhingas, manatees and alligators. Back home in Nova Scotia before the end of January, I found new resonances in Bishop’s “Seascape,” with its “white herons got up as angels, / flying as high as they want and as far as they want sideways,” and “the suggestively Gothic arches of the mangrove roots.” It’s easy to imagine that Bishop, so drawn to Florida’s natural spaces, would’ve been pleased that a reader of her poetry spent much more time gazing at unfamiliar flora and fauna than standing on sidewalks outside her Key West residences.

_______________________________________

Biographical details in this essay derive from Elizabeth Bishop,

One Art: Letters, ed. Robert Giroux

(Farrar Straus Giroux, 1994); Brent C. Millier, Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It (U of California P,

1993); Thomas Travisano, Love Unknown:

The Life and Worlds of Elizabeth Bishop (Viking, 2019).

Thursday, February 8, 2024

Interest in Elizabeth Bishop stronger than ever -- and HAPPY BIRTHDAY EB!

On this day 113 years ago, Elizabeth Bishop was born in Worcester, MA. Her stature as one of the most important American poets of the 20th century remains solid. Last fall, Vassar College mounted an exhibit, “Elizabeth Bishop’s Postcards,” that received glowing reviews in major literary journals. We understand that a number of venues have expressed interest in hosting this exhibit in the future. A full-dress biography is in the works by the American Merrill biographer Langdon Hammer. The Bishop-Lowell Studies, an academic journal dedicated to fostering scholarship about Bishop and Robert Lowell has been publishing for several years. And the Elizabeth Bishop Society in the U.S. continues to connect Bishop scholars around the world. The Elizabeth Bishop House in Key West is being restored and will be come the headquarters of the Key West Literary Seminar. This June will see a symposium about her taking place in Glasgow, Scotland.

On a more local level, the Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia turns 30 this year and there will be activities marking this milestone in Great Village in June. And the Elizabeth Bishop House in the village continues to welcome writers and artists as a place of retreat and a venue for readings and workshops.

As

information about the EBSNS events unfold, we will post them here and on our

other social media.

Tuesday, November 28, 2023

Elizabeth Bishop in Glasgow: A Symposium (26th to 28th June 2024) Early Announcement and Call for Papers

The University of Glasgow, College of Arts & Humanities, is delighted to welcome the 2024 Elizabeth Bishop Symposium to our beautiful, historic and friendly city. Following on from similar events in Oxford, Paris and Sheffield, Elizabeth Bishop in Glasgow provides an opportunity both to hear about recent and emerging work in Bishop Studies, and to consider Bishop’s writing in a Scottish Atlantic context – a legacy that helped to shape the history and culture of Great Village, Nova Scotia, Bishop’s maternal family home and her imaginative lodestone. Bishop was familiar from childhood with the poetry of Robert Burns (and had editions of his work in her adult library); our Symposium will consider the influence of Burns – and of other Scottish writers and artists – on Bishop’s writing. And it will ask, in turn, about Bishop’s influence on her successors in Scotland up to the present day.

Confirmed speakers include Professor Langdon Hammer (Yale University) and Victoria Fox (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

Elizabeth Bishop in Glasgow is open to anyone with an interest in Bishop’s life, work and reception; in modern poetry; in Scottish and American literature and culture, in the Scottish Atlantic and in related fields. We welcome proposals for short papers (c. 20 minutes) or other forms of participation on these and related themes. Other areas of focus might include (but are not limited to):

Boundaries

Travel and walking

The North

Mystery

Bishop’s correspondence

Religion, Protestantism, the Bible

Language: Gaelic and Scots

Music, Scottish Song, hymns

Diaspora

The Atlantic

Trade

Scottish Atlantic slavery

Publishing history

Visual culture

Bishop’s contemporaries

Bishop’s influence

Bishop in / and translation

Gender and sexuality

Robert Burns, Alexander Selkirk, Thomas and Jane Carlyle

Please send brief proposals for papers, panels (3 contributors) or other forms of participation to: vp-arts@glasgow.ac.uk by MONDAY 15th JANUARY 2024.

Location: Elizabeth Bishop in Glasgow will take place in the

James McCune Smith Building on the University of Glasgow’s main (Gilmorehill)

campus in the lively West End of Glasgow and will open on the morning of Weds

26th June and close after lunch on Fri 28th . The booking page will open

shortly. There will be time in the programme to visit the Hunterian Art

Gallery, the Hunterian Museum or the Charles Rennie Mackintosh House. The

campus is easily accessible by bus or subway from the city centre and there are

hotels, guesthouses and restaurants close by.

Organisers and Steering Group: Jo Gill (University of Glasgow); Jonathan Ellis (University of Sheffield); Angus Cleghorn (Seneca College); Bethany Hicok (Williams College); Tom Travisano (Hartwick College).

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

Kafka, Bishop and Literary Pilgrimage: A response to Elana Wolff’s Faithfully Seeking Franz

“Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? / Where should we be today?” — Elizabeth Bishop, “Questions of Travel”

Sometime in the late 1990s, I was sitting in Trident café in downtown Halifax with the writer and broadcaster Jane Kansas and a young friend of hers, whose name I forget. Jane and I were having a lively conversation about our literary passions — hers: the American writer Harper Lee; mine: Elizabeth Bishop (“3/4ths Nova Scotian and 1/4th New Englander,” or a “herring-choker Bluenoser,” as Bishop described herself to Anne Stevenson). As I remember the conversation, it was animated, with a lot of talk about original sources, such as letters; and also about going to places that were important to these writers. The young friend sat quietly listening to us until at one point she blurted out, in a rather disgusted tone, “You are literary stalkers.” We paused and looked at her. I was surprised by this characterization, but as I thought about it, I couldn’t discount the assessment. I had already made several Bishop pilgrimages (Great Village, Vassar College, Worcester) and was mining her letters and archival documents for information about her life. Jane and I argued that what we were doing wasn’t intrusive, rather an honouring — not an invasion of privacy — but of course on some level it was. Harper Lee (still alive then) was a known recluse. Bishop, long dead, was regarded as a very private person, having once declared to a friend she perferred “closets, closets and more closets.” (OB 327) I have never forgotten that conversation and have endeavoured ever since to conduct my research and writing about Bishop in the most respectful manner. Not sure that made what I did any less objectionable, but I took solace in knowing that Bishop herself was keenly interested in the lives of the writers she read.

While Bishop said she wasn’t a fan of “German art,” its “heaviness,” she had been a reader of Kafka since her adolescence. In a 1949 letter to Robert Lowell, she noted: “I’m glad you like ‘In Prison.’ I had only read The Castle of Kafka when I wrote it, and that long before, so I don’t know where it [her story] came from.” (OA 182) And in a 1958 letter again to Lowell, writing about her response to some “short instrumental pieces” by Webern she had just heard, she noted how much she liked them, “That strange kind of modesty that I think one feels in almost everything contemporary one really likes — Kafka, say, or Marianne [Moore], or even Eliot, and Klee and Kokoschka and Schwitters … Modesty, care, space, a sort of helplessness but determination at the same time.” (WIA 250)

As noted above, Bishop was interested in the lives of the artists she admired, so I can’t help but think she would find the new book by Toronto writer Elana Wolff, Faithfully Seeking Franz, intriguing. Just published by Guernica Editions, Wolff’s book is a collection of poems and prose pieces about her search for Kafka in the places that were significant to him. I can certainly appreciate such a compulsion. So when this book came to hand, I was keen to read it. I have enjoyed every page. Each journey, encounter and account conveys not mere “compulsion” but deep, abiding and respectful dedication, devotion even, to understanding the meaning of Kafka’s work, Kafka’s life in his work, Kafka’s impact on posterity, especially on the young woman who read first The Castle and took its impact with her for the rest of her life, following in the footsteps of a compelling mystery:

Yet having taken steps the author took; steps his ciphers, stand-ins, and characters also took; in seeing and feeling convergences of life and art on location, in company with M., in triangulation with ‘atemporal-aspatial’ Kafka, through signs, signals, messages, indications and ‘visitations’ — through these, the experience of reading has become heightened and deepened, ‘lived into’. Questing has whetted the appetite for more. I’ve become compulsively recursive in my search. I can’t settle. (263)

As a fellow pilgrim, I could identify with every word of this passage. The identifier in Bishop’s work would be from “Sandpiper”: “poor bird, he is obsessed.” But I prefer to call it passionate, and Elana Wolff’s passion unfolds in the most delightful, insightful, unexpected ways. We follow her footsteps and in so doing, not only learn about Kafka, but also begin to understand what the power of art really is. Connection, coincidence, conundrum: all are experiences along the way; and accompanying it all: questions, surprising revelations, satisfying and disappointing conclusions. Such is life itself.

In a world filled with chaos and violence and uncertainty, art matters. How so is such a complex and mysterious condition that it cannot be distilled or confined. Wolff never tries to delimit this mystery, even as she charts borders and boundaries (geographical, physiological, aesthetic, existential). One of the many things I admire about Faithfully Seeking Franz is its “Un-endness” (261):

Invisible and thin and

free,

as baffling as Kafka —

whose rendering of

difficult things

was easier for him, it

seems to me,

than birthing breath.

Will teachers of any persuasion contravene me? (285)

Wednesday, September 20, 2023

Key West Sketches now available

The folks of the Key West Literary Seminar have some news to share:

We are thrilled to announce the publication of Key West Sketches: Writers at Mile Zero, a new anthology out today from Blair. Edited by Carey Winfrey, the former editor-in-chief of Smithsonian magazine and longtime KWLS board member, the 250-page volume tracks Key West's extraordinary and eclectic literary history. The book's many treasures include Thomas McGuane's account of a long-ago dinner with Tennessee Williams; Elizabeth Bishop's description of Key West folk painter Gregorio Valdes; Joy Williams on Ernest Hemingway in Key West; and Judy Blume's real-life story of becoming a bookstore owner-operator at the end of the road. There are poems by Billy Collins and James Merrill; heart-rending recollections of Harry Mathews by Ann Beattie; Richard Wilbur by Phyllis Rose; and David Wolkowsky by William Wright. And so much more, with contributions from Pico Iyer, Philip Caputo, Daniel Menaker, Brian Antoni, Alison Lurie, and many others.

Friday, September 8, 2023

A stay in the Elizabeth Bishop House

My sister and I were fortunate to spend a week at the EB House from 21 to 26 August. What a privilege it was to be back in the village for a sojourn that included lots of company and visiting with friends, who we see seldomly these days, and to sit for long stretches on the verandah and watch the big sky, the lush green meadow. We saw lots of birds and deer. We are deeply grateful to Laurie Gunn and the St. James Church of Great Village Preservation Society. They are looking after the house so well and it is wonderful to know that writers and artists from all over still get to stay there.

I will admit that my heart aches whenever I drive into the village and see that the piercing steeple of the church is gone. Well, it now sits quietly beside the building which once it topped, anchored by concrete blocks, its beautiful lightning rod so much closer to the ground. Life is change, but some changes are harder to come to terms with than others. How I wish that the funds could be found to replace and restore it, but that would require a significant effort and expense, I am sure. I am glad to see that the steeple is still appreciated, and occupying a prominent spot under a canopy of trees.

Here are a

few photos taken by my sister, Brenda Barry, during our visit.

Saturday, September 2, 2023

“Out of the Ninth-Month Midnight”

In

memoriam, Flight 111 (2 September 1998)

Late afternoon, wind off the land.

Mountainous

clouds backlit by sun.

The

water is quicksilver.

Systaltic

─ now and then, now and then.

The

harbour is a heart, whole

and shattered,

held together,

torn

apart by its own pulse ─

the

circle of sun, the season,

the

millennium.

Suddenly,

two quivers of light

as

though far away has epitomized.

Plovers,

a pair, semipalmated,

winter-ready,

rare

on

this bit of beach at the Point.

My

gaze caught on their bright white

airborne

bellies;

I

follow them to the shoreline.

They

become stones.

Have

they come to answer the question

I ask

of the Atlantic?

They

have come to rest in the midst

of

their imperative ─

the

space between them

is the

moment between contractions

when

eternity relaxes

and

the chambers of the world

fill

with silence.

With

my binoculars I see their dark

brown

eyes keeping watch,

the

single dark breast bands,

the

nearly all dark beaks.

So

still, so alert

they

are perfectly aware of survival’s

fragility.

They simply know

the

temperature of tomorrow.

It is

me who holds us

inside

a compass,

a

dial; but there is no circumference

except

what I need to cradle

my

desperate longing.

Time

is broken and mended

in

every breath, and the ocean

ticks

strangely in the blood...

Here,

on a September littoral,

where

late afternoon sun slants seaward,

with a

warm wind blowing off the land,

on a

long journey between now and then,

these

two together pause

because life and death will not.

Tuesday, July 11, 2023

Summer poetry reading at the EB House

I had the great privilege and honour to read with three exceptional poets on Saturday, 8 July 2023, in Great Village, N.S., at the Elizabeth Bishop House: Rosaria Campbell, Kalya Geitzler and Margo Wheaton. Over 25 people attended – a lively gathering if ever there was one. I hope everyone had as nice a time as I did. I am so grateful that once again such in person convegences are possible. Ever so uplifting to meet with friends and strangers and share poetry, especially in such a beloved setting as the EB House. Here are a few photos of the event.

(Rosaria Campbell reading. Photo by Brenda Barry.)

(Kayla Geitzler reading. Photo by Brenda Barry)

(Margo Wheaton reading. Photo by Brenda Barry)

The quartet on the verandah of the EB House.

Standing: Kayla and Rosaria; seated: Margo and Sandra

(Photo by Roxanne Smith)

Thursday, June 22, 2023

Poetry reading at Elizabeth Bishop House

On Saturday 8 July, a poetry reading will take place at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, N.S. The poets reading are Sandra Barry, Rosaria Campbell, Kayla Geitzler and Margo Wheaton. Learn more about the reading on its Facebook event page.

Monday, June 19, 2023

EBSNS holds its 2023 Annual General Meeting in Great Village, N.S.

For the first time in its history, the EBSNS held its AGM in the Elizabeth Bishop House. A merry band of 20 members and guests gathered for a lively afternoon of business, an uplifting presentation and delicious treats. You can read the minutes and see other documents connected to the business side of things on the EBSNS website.

The highlight of the afternoon was a fascinating presentation by writer Rita Wilson and illustrator Emma FitzGerald, who collaborated on A Pocket of Time: The Poetic Childhood of Elizabeth Bishop, published by Nimbus Publishing in 2019. They shared rich descriptions and details of their respective creative processes, which lead to a timeless book about Bishop’s childhood in Great Village. The assembled sat with rapt attention as both artists shared the often surprising path that brought the book into being. The location was perfect for the presentation, as the book is set mostly in the house. We all felt the magic of being in the place that meant so much to Bishop. After the presentation, Rita and Emma conducted an exercise with the audience, having them draw pictures connected to memories of childhood. Lots of questions were asked that generated lively discussion.

Here are a few photos of the gathering.

N.B.: 2024 will mark the 30th anniversary of the Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia. The EBSNS board is planning a series of events at the EB House in June next year to mark this milestone. More information about these events will be posted as it becomes available.

********************************************************************

One of the new additions to the EB House is a hand-made hooked rug done by Colchester fabric artist Penny Lighthall, based on Bishop’s poem “First Death in Nova Scotia.” Appropriately, it has been placed in the parlour. You can learn more about Penny’s work on her Facebook pages. Thanks to Penny for giving such a delightful gift to the EB House. Rug hooking was an art form that Bishop's maternal grandmother and aunts engaged in regularly. She noted in a letter to a friend that the house was full of such rugs.

Saturday, May 27, 2023

EB event on 1 June 2023

Grolier's Poetry Book Shop in Cambridge, MA, will host a Bishop conversation (in person and virtual) on 1 June at 7 p.m. Click here to learn how to register: Upcoming Readings — Grolier Poetry Book Shop

Monday, May 1, 2023

Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia 2023 Annual General Meeting

EBSNS Annual General Meeting

Saturday, 17 June 2023, 1:30 p.m.

Elizabeth Bishop House,

Great Village, N.S.

No admission. Everyone is

welcome!

Special guests will be writer Rita Wilson, author of A Pocket of Time: The Poetic Childhood of Elizabeth Bishop, and the book’s illustrator Emma FitzGerald. They will talk about the creative process for this delightful and important book about Bishop’s deep and abiding connection to Great Village.

Monday, April 10, 2023

New additions to the Elizabeth Bishop House

Some years ago (pre-pandemic), the EBSNS set up an exhibit of Elizabeth Bishop and Bulmer family artefacts in the sanctuary of St. James Church in Great Village, N.S. It remained there, with items being changed periodically, ever since. Recently, the church was sold and is now in private hands, the sanctuary being transformed into a concert space. The EBSNS decided that it was now time to move the exhibit to another place. The board is delighted to report that this new place is the Elizabeth Bishop House in the village. The principal elements of the exhibit were two stunning hand-made cabinets built by Great Village carpenter Garry Shears. Early in April 2023, EB House administrator Laurie Gunn secured the assistance of several strong fellows and the cabinets and their contents were removed from the church and taken across the road to the EB House. A minor adjustment was required to the larger cabinet, so it would fit, which Garry Shears kindly did – and now both cabinets are installed in the house. The larger cabinet is in the front room (the good parlour). The smaller cabinet was put on the upstairs landing. The EBSNS board wishes to thank all those who had a hand in this transfer. That it was done so quickly is all due to Laurie Gunn. While not as public a space as the original location, it is felt that the cabinets and their precious artefacts are now in a safe space, and one that is entirely appropriate to them. Here are a few photos of the cabinets in situ.

Monday, February 20, 2023

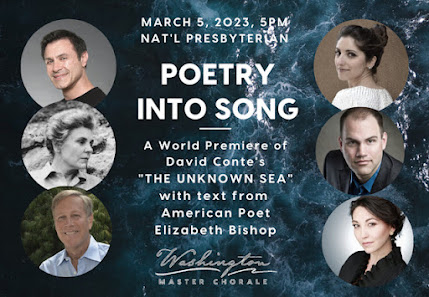

World premiere of new Elizabeth Bishop inspired choral work

Word just in from the Elizabeth Bishop Society in the US: We are pleased to announce the world premiere of a choral work titled The Unknown Sea by renowned composer David Conte. This new choral orchestral work is inspired by the texts of the poet Elizabeth Bishop and will feature mezzo soprano Lena Seikaly, chorus, piano, and chamber orchestra. Conte himself will be in attendance and participate in a pre-concert conversation led by the former Poet Laureate of California, Dana Gioia.

The concert will be performed by the Washington Master Chorale

and will be held on March 5, 2023, at 5:00 PM at Washington’s National

Presbyterian Church, at 4101 Nebraska Avenue, NY in Washington, DC.

According to the Master Chorale, "The Unknown Sea

will be paired with Ralph Vaughan Williams’s masterful cantata, Dona Nobis

Pacem based on Walt Whitman’s poems, as well as texts from the

Hebrew Bible and Latin Mass.”

This world premiere was originally planned for the spring of

2020, but the premiere was delay by the outbreak of Covid. We are very pleased

that the event will now be held.

More information may be obtained by contacting Travis Hare: travis@kendrarubinfeldpr.com

Friday, February 17, 2023

Sable Island “Total Immersion”: A response to “Geographies of Solitude”

On Wednesday evening, 15 February 2023, at King’s Theatre in Annapolis Royal, N.S., I had the privilege of attending a screening of “Geographies of Solitude,” film-maker Jacquelyn Mills’s stunning documentary about Sable Island and its long-time “inhabitant” Zoe Lucas, who first arrived on the island in 1971, and who has spent time there every year since then.

“Geographies of Solitude” is a visual and sonic feast, an intimate and profound exploration

of Zoe’s decades-long connection to one of the most mythical and historical

islands of Canada. At once richly factual and breath-takingly lyrical, by turns

earthy and ethereal.

I met Zoe

about 20 years ago and thanks to her invitation, I had the even greater

privilege of going to Sable Island in May 2008, with our mutual friend Janet

Barkhouse. I was there only for a day, but it was a day I will never forget, a

trip of a life-time. I was keen to see Mills’s film and was thrilled by its

scope, from the microscopic to the celestial, the great sweep of the island and

the ocean were the backdrop for an unfolding of Zoe’s remarkable work

(research, recording, education, advocacy) that includes geology, meteorology,

zoology, botany, etc. She has been involved in one way or another with all the

research work that has happened on Sable Island in the past half-century.

One of the

many reasons I wanted to go to Sable Island was that Elizabeth Bishop visited

there in 1951. Her great-grandfather

Robert Hutchinson had been shipwrecked out there in 1866 and she was keen to

see the Ipswich Sparrow, which nests only Sable Island. Her intention was to

write a piece about the island for The New Yorker, which she tentatively

titled “The Deadly Sandpile,” an acknowledgement of its more famous moniker,

“The Graveyard of the Atlantic.” Sadly, she never finished the piece; but her

interest in the island remained with her for the rest of her life.

Zoe’s first

landfall there in 1971 overlapped for a few years with Bishop, who died in

1979. I like to think Bishop would have been as intrigued, as thousands are,

about this young woman who ended up devoting her life to the place and the

cause of Sable Island and environmentalism in general. Towards the end of the

film, Zoe observes that there wasn’t an actual single decision she made that

put her there, but a series of small decisions that in and of themselves didn’t

mean much, but added up: then “something happens.” This idea about how life

unfolds was one Bishop herself shared.

Mills’s

film, shot on 16 and 35mm film, is a feast for the eyes and ears. The

soundscape is especially rich and vibrant, even at times a bit overwhelming

(which is saying a lot because the images are astonishing, one after another

after another). One fascinating expression is the sound of invertebrates

walking: beetles, snails, ants — somehow Mills was able to bore down

into what is inaudible to human ears (especially in an environment like Sable

where the wind blows and waves crash continuously). And then somehow, using

magical technology, the sounds of these creatures moving is transformed into

music! Bishop was passionate herself about music and would have been awed by

this wonderful gesture in the film. We also hear the horses, the seals, the

birds (one newborn seal sounds hauntingly like a human baby – we are not

separate from the natural world, though our daily, political and social realms

often create walls/barriers that keep us from feeling the connections — and to our peril).

And most

importantly we hear Zoe talking about her connections to the island — the history of her time there, details about her work, reflections on

all manner of experiences. All the while we follow her on purposeful wanderings

across the dunes and beaches, hearing that wind blow, while, pen and notebook

in hand, she records everything she sees and finds; and we sit with her in her

inner work spaces — sorting and washing garbage,

inputting data into colossal spread sheets that are searchable by dozens of

categories.

There is so

much glory and tragedy and mystery connected to Sable Island and Zoe has

thought about all of it, noting at one point that after decades of living

there, she still can come upon something and say, “Wow!” That actually happens

in the film when she finds an especially large (terrifying) spider among some

flora and puts it in a specimen jar. Exciting!

Of course,

the horses are the great wonder of the island (even more so than the tens of

thousands of seals that congregate there to have their pups) – and Mills gives

us a great dose of them in all their splendor – in life and death. Mills does

not look away from the natural cycle of life on the island, which is uplifting,

rather than sad. What is sad and deeply troubling, however, is the garbage that

Zoe has been collecting and documenting minutely for decades. Mills makes us

look right into the heart of the results of our gross consumption and

disposable society. Zoe has been recording this impact long before there was

the global consciousness of the immeasurable amount of plastics in our oceans.

To account

for all the elements in this intimately shot, intricately woven documentary is

not possible — it must be seen because it is

immersive. But there are often distilled, crystalized moments, always

thought-provoking, that shine. For me, one of the most delightful is the

archival footage of Jacques Cousteau in 1981 landing on Sable Island in the

helicopter from “The Calypso,” being greeted by a young Zoe Lucas, who takes

him on a tour. How cool is that!

Bravo to Mills for doing her own “total immersion” on Sable Island, looking through her lens so directly and deeply at the wondrous scope (temporal, physical, existential) of this unique place on our planet. A few years ago, Zoe and other keen supporters of her work and of Sable Island formed the Sable Island Institute. I was glad to see the institute so directly mentioned at the end of this film. Check out its website and learn more; this site is also a “total immersion” — among many things, it shares dozens of Zoe’s astonishing photos of the island. I suggest that Zoe has taken more photos of it, collected more diverse data about it, and has shared more knowledge and insights about the island than any other person on the planet. It was a good thing, for us all, that she just happened to end up there!

.png)